- Home

- Samuel Beckett

Three Novels Page 3

Three Novels Read online

Page 3

Such were my thoughts as I waited for my son to come back and Gaber, whom I had not yet heard leave, to go. And tonight I find it strange I could have thought of such things, I mean my son, my lack of breeding, Father Ambrose, Verger Joly with his register, at such a time. Had I not something better to do, after what I had just heard? The fact is I had not yet begun to take the matter seriously. And I am all the more surprised as such light-mindedness was not like me. Or was it in order to win a few more moments of peace that I instinctively avoided giving my mind to it? Even if, as set forth in Gaber’s report, the affair had seemed unworthy of me, the chief’s insistence on having me, me Moran, rather than anybody else, ought to have warned me that it was no ordinary one. And instead of bringing to bear upon it without delay all the resources of my mind and of my experience, I sat dreaming of my breed’s infirmities and the singularities of those about me. And yet the poison was already acting on me, the poison I had just been given. I stirred restlessly in my armchair, ran my hands over my face, crossed and uncrossed my legs, and so on. The colour and weight of the world were changing already, soon I would have to admit I was anxious.

I remembered with annoyance the lager I had just absorbed. Would I be granted the body of Christ after a pint of Wallenstein? And if I said nothing? Have you come fasting, my son? He would not ask. But God would know, sooner or later. Perhaps he would pardon me. But would the eucharist produce the same effect, taken on top of beer, however light? I could always try. What was the teaching of the Church on the matter? What if I were about to commit sacrilege? I decided to suck a few peppermints on the way to the presbytery.

I got up and went to the kitchen. I asked if Jacques was back. I haven’t seen him, said Martha. She seemed in bad humour. And the man? I said. What man? she said. The man who came for a glass of beer, I said. No one came for anything, said Martha. By the way, I said, unperturbed apparently, I shall not eat lunch today. She asked if I were ill. For I was naturally a rather heavy eater. And my Sunday midday meal especially I always liked extremely copious. It smelt good in the kitchen. I shall lunch a little later today, that’s all, I said. Martha looked at me furiously. Say four o’clock, I said. In that wizened, grey skull what raging and rampaging then, I knew. You will not go out today, I said coldly, I regret. She flung herself at her pots and pans, dumb with anger. You will keep all that hot for me, I said, as best you can. And knowing her capable of poisoning me I added, You can have the whole day off tomorrow, if that is any good to you.

I left her and went out on the road. So Gaber had gone without his beer. And yet he had wanted it badly. It was a good brand, Wallenstein. I stood there on the watch for Jacques. Coming from church he would appear on my right, on my left if he came from the slaughter-house. A neighbour passed. A free-thinker. Well well, he said, no worship today? He knew my habits, my Sunday habits I mean. Everyone knew them and the chief perhaps better than any, in spite of his remoteness. You look as if you had seen a ghost, said the neighbour. Worse than that, I said, you. I went in, at my back the dutifully hideous smile. I could see him running to his concubine with the news, You know that poor bastard Moran, you should have heard me, I had him lepping! Couldn’t speak! Took to his heels!

Jacques came back soon afterwards. No trace of frolic. He said he had been to church alone. I asked him a few pertinent questions concerning the march of the ceremony. His answers were plausible. I told him to wash his hands and sit down to his lunch. I went back to the kitchen. I did nothing but go to and fro. You may dish up, I said. She had wept. I peered into the pots. Irish stew. A nourishing and economical dish, if a little indigestible. All honour to the land it has brought before the world. I shall sit down at four o’clock, I said. I did not need to add sharp. I liked punctuality, all those whom my roof sheltered had to like it too. I went up to my room. And there, stretched on my bed, the curtains drawn, I made my first attempt to grasp the Molloy affair.

My concern at first was only with its immediate vexations and the preparations they demanded of me. The kernel of the affair I continued to shirk. I felt a great confusion coming over me.

Should I set out on my autocycle? This was the question with which I began. I had a methodical mind and never set out on a mission without prolonged reflection as to the best way of setting out. It was the first problem to solve, at the outset of each enquiry, and I never moved until I had solved it, to my satisfaction. Sometimes I took my autocycle, sometimes the train, sometimes the motor-coach, just as sometimes too I left on foot, or on my bicycle, silently, in the night. For when you are beset with enemies, as I am, you cannot leave on your autocycle, even in the night, without being noticed, unless you employ it as an ordinary bicycle, which is absurd. But if I was in the habit of first settling this delicate question of transport, it was never without having, if not fully sifted, at least taken into account the factors on which it depended. For how can you decide on the way of setting out if you do not first know where you are going, or at least with what purpose you are going there? But in the present case I was tackling the problem of transport with no other preparation than the languid cognizance I had taken of Gaber’s report. I would be able to recover the minutest details of this report when I wished. But I had not yet troubled to do so, I had avoided doing so, saying, The affair is banal. To try and solve the problem of transport under such conditions was madness. Yet that was what I was doing. I was losing my head already.

I liked leaving on my autocycle, I was partial to this way of getting about. And in my ignorance of the reasons against it I decided to leave on my autocycle. Thus was inscribed, on the threshold of the Molloy affair, the fatal pleasure principle.

The sun’s beams shone through the rift in the curtains and made visible the sabbath of the motes. I concluded from this that the weather was still fine and rejoiced. When you leave on your autocycle fine weather is to be preferred. I was wrong, the weather was fine no longer, the sky was clouding over, soon it would rain. But for the moment the sun was still shining. It was on this that I went, with inconceivable levity, having nothing else to go on.

Next I attacked, according to my custom, the capital question of the effects to take with me. And on this subject too I should have come to a quite otiose decision but for my son, who burst in wanting to know if he might go out. I controlled myself. He was wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, a thing I do not like to see. But there are nastier gestures, I speak from experience.

Out? I said. Where? Out! Vagueness I abhor. I was beginning to feel hungry. To the Elms, he replied. So we call our little public park. And yet there is not an elm to be seen in it, I have been told. What for? I said. To go over my botany, he replied. There were times I suspected my son of deceit. This was one. I would almost have preferred him to say, For a walk, or, To look at the tarts. The trouble was he knew far more than I, about botany. Otherwise I could have set him a few teasers, on his return. Personally I just liked plants, in all innocence and simplicity. I even saw in them at times a superfetatory proof of the existence of God. Go, I said, but be back at half-past four, I want to talk to you. Yes papa, he said. Yes papa! Ah!

I slept a little. Faster, faster. Passing the church, something made me stop. I looked at the door, baroque, very fine. I found it hideous. I hastened on to the presbytery. The Father is sleeping, said the servant. I can wait, I said. Is it urgent? she said. Yes and no, I said. She showed me into the sitting-room, bare and bleak, dreadful. Father Ambrose came in, rubbing his eyes. I disturb you, Father, I said. He clicked his tongue against the roof of his mouth, protestingly. I shall not describe our attitudes, characteristic his of him, mine of me. He offered me a cigar which I accepted with good grace and put in my pocket, between my fountain-pen and my propelling-pencil. He flattered himself, Father Ambrose, with being a man of the world and knowing its ways, he who never smoked. And everyone said he was most broad. I asked him if he had noticed my son at the last mass. Certainly, he said, we even spoke together. I must have looked surprised.

Yes, he said, not seeing you at your place, in the front row, I feared you were ill. So I called for the dear child, who reassured me. A most untimely visitor, I said, whom I could not shake off in time. So your son explained to me, he said. He added, But let us sit down, we have no train to catch. He laughed and sat down, hitching up his heavy cassock. May I offer you a little glass of something? he said. I was in a quandary. Had Jacques let slip an allusion to the lager. He was quite capable of it. I came to ask you a favour, I said. Granted, he said. We observed each other. It’s this, I said, Sunday for me without the Body and Blood is like—. He raised his hand. Above all no profane comparisons, he said. Perhaps he was thinking of the kiss without a moustache or beef without mustard. I dislike being interrupted. I sulked. Say no more, he said, a wink is as good as a nod, you want communion. I bowed my head. It’s a little unusual, he said. I wondered if he had fed. I knew he was given to prolonged fasts, by way of mortification certainly, and then because his doctor advised it. Thus he killed two birds with one stone. Not a word to a soul, he said, let it remain between us and—. He broke off, raising a finger, and his eyes, to the ceiling. Heavens, he said, what is that stain? I looked in turn at the ceiling. Damp, I said. Tut tut, he said, how annoying. The words tut tut seemed to me the maddest I had heard. There are times, he said, when one feels like weeping. He got up. I’ll go and get my kit, he said. He called that his kit. Alone, my hands clasped until it seemed my knuckles would crack, I asked the Lord for guidance. Without result. That was some consolation. As for Father Ambrose, in view of his alacrity to fetch his kit, it seemed evident to me he suspected nothing. Or did it amuse him to see how far I would go? Or did it tickle him to have me commit a sin? I summarised the situation briefly as follows. If knowing I have beer taken he gives me the sacrament, his sin, if sin there be, is as great as mine. I was therefore risking little. He came back with a kind of portable pyx, opened it and dispatched me without an instant’s hesitation. I rose and thanked him warmly. Pah! he said, it’s nothing. Now we can talk.

I had nothing else to say to him. All I wanted was to return home as quickly as possible and stuff myself with stew. My soul appeased, I was ravenous. But being slightly in advance of my schedule I resigned myself to allowing him eight minutes. They seemed endless. He informed me that Mrs. Clement, the chemist’s wife and herself a highly qualified chemist, had fallen, in her laboratory, from the top of a ladder, and broken the neck—. The neck! I cried. Of her femur, he said, can’t you let me finish. He added that it was bound to happen. And I, not to be outdone, told him how worried I was about my hens, particularly my grey hen, which would neither brood nor lay and for the past month and more had done nothing but sit with her arse in the dust, from morning to night. Like Job, haha, he said. I too said haha. What a joy it is to laugh, from time to time, he said. Is it not? I said. It is peculiar to man, he said. So I have noticed, I said. A brief silence ensued. What do you feed her on? he said. Corn chiefly, I said. Cooked or raw? he said. Both, I said. I added that she ate nothing any more. Nothing! he cried. Next to nothing, I said. Animals never laugh, he said. It takes us to find that funny, I said. What? he said. It takes us to find that funny, I said loudly. He mused. Christ never laughed either, he said, so far as we know. He looked at me. Can you wonder? I said. There it is, he said. He smiled sadly. She has not the pip, I hope, he said. I said she had not, certainly not, anything he liked, but not the pip. He meditated. Have you tried bicarbonate? he said. I beg your pardon? I said. Bicarbonate of soda, he said, have you tried it? Why no, I said. Try it! he cried, flushing with pleasure, have her swallow a few dessertspoonfuls, several times a day, for a few months. You’ll see, you won’t know her. A powder? I said. Bless my heart to be sure, he said. Many thanks, I said, I’ll begin today. Such a fine hen, he said, such a good layer. Or rather tomorrow, I said. I had forgotten the chemist was closed. Except in case of emergency. And now that little cordial, he said. I declined.

This interview with Father Ambrose left me with a painful impression. He was still the same dear man, and yet not. I seemed to have surprised, on his face, a lack, how shall I say, a lack of nobility. The host, it is only fair to say, was lying heavy on my stomach. And as I made my way home I felt like one who, having swallowed a pain-killer, is first astonished, then indignant, on obtaining no relief. And I was almost ready to suspect Father Ambrose, alive to my excesses of the forenoon, of having fobbed me off with unconsecrated bread. Or of mental reservation as he pronounced the magic words. And it was in vile humour that I arrived home, in the pelting rain.

The stew was a great disappointment. Where are the onions? I cried. Gone to nothing, replied Martha. I rushed into the kitchen, to look for the onions I suspected her of having removed from the pot, because she knew how much I liked them. I even rummaged in the bin. Nothing. She watched me mockingly.

I went up to my room again, drew back the curtains on a calamitous sky and lay down. I could not understand what was happening to me. I found it painful at that period not to understand. I tried to pull myself together. In vain. I might have known. My life was running out, I knew not through what breach. I succeeded however in dozing off, which is not so easy, when pain is speculative. And I was marvelling, in that half-sleep, at my half sleeping, when my son came in, without knocking. Now if there is one thing I abhor, it is someone coming into my room, without knocking. I might just happen to be masturbating, before my cheval-glass. Father with yawning fly and starting eyes, toiling to scatter on the ground his joyless seed, that was no sight for a small boy. Harshly I recalled him to the proprieties. He protested he had knocked twice. If you had knocked a hundred times, I replied, it would not give you the right to come in without being invited. But, he said. But what? I said. You told me to be here at half-past four, he said. There is something, I said, more important in life than punctuality, and that is decorum. Repeat. In that disdainful mouth my phrase put me to shame. He was soaked. What have you been looking at? I said. The liliaceae, papa, he answered. The liliaceae papa! My son had a way of saying papa, when he wanted to hurt me, that was very special. Now listen to me, I said. His face took on an expression of anguished attention. We leave this evening, I said in substance, on a journey. Put on your school suit, the green—. But it’s blue, papa, he said. Blue or green, put it on, I said violently. I went on. Put in your little knapsack, the one I gave you for your birthday, your toilet things, one shirt, one pair of socks and seven pairs of drawers. Do you understand? Which shirt, papa? he said. It doesn’t matter which shirt, I cried, any shirt! Which shoes am I to wear? he said. You have two pairs of shoes, I said, one for Sundays and one for weekdays, and you ask me which you are to wear. I sat up. I want none of your lip, I said.

Thus to my son I gave precise instructions. But were they the right ones? Would they stand the test of second thoughts? Would I not be impelled, in a very short time, to cancel them? I who never changed my mind before my son. The worst was to be feared.

Where are we going, papa? he said. How often had I told him not to ask me questions. And where were we going, in point of fact. Do as you’re told, I said. I have an appointment with Mr. Py tomorrow, he said. You’ll see him another day, I said. But I have an ache, he said. There exist other dentists, I said, Mr. Py is not the unique dentist of the northern hemisphere. I added rashly, We are not going into the wilderness. But he’s a very good dentist, he said. All dentists are alike, I said. I could have told him to get to hell out of that with his dentist, but no, I reasoned gently with him, I spoke with him as with an equal. I could furthermore have pointed out to him that he was lying when he said he had an ache. He did have an ache, in a bicuspid I believe, but it was over. Py himself had told me so. I have dressed the tooth, he said, your son cannot possibly feel any more pain. I remembered this conversation well. He has naturally very bad teeth, said Py. Naturally, I said, what do you mean, naturally? What are you insinuating? He was born with bad teeth, said Py, and all his life he will have bad teeth. Naturally I shall do what I c

an. Meaning, I was born with the disposition to do all I can, all my life I shall do all I can, necessarily. Born with bad teeth! As for me, I was down to my incisors, the nippers.

More Pricks Than Kicks

More Pricks Than Kicks Happy Days

Happy Days Breath, and Other Shorts

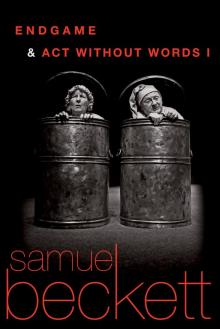

Breath, and Other Shorts Endgame & Act Without Words

Endgame & Act Without Words The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett

The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989

The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989 Stories and Texts for Nothing

Stories and Texts for Nothing Waiting for Godot

Waiting for Godot Rockaby and Other Short Pieces

Rockaby and Other Short Pieces First Love and Other Shorts

First Love and Other Shorts How It Is

How It Is Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment

Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment Echo's Bones

Echo's Bones Texts for Nothing and Other Shorter Prose 1950-1976

Texts for Nothing and Other Shorter Prose 1950-1976 Three Novels

Three Novels Murphy

Murphy Mercier and Camier

Mercier and Camier Eleuthéria

Eleuthéria Selected Poems 1930-1988

Selected Poems 1930-1988 Dream of Fair to Middling Women

Dream of Fair to Middling Women Watt

Watt Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces

Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces The Complete Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett

The Complete Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Worstward Ho

Worstward Ho Collected Poems in English and French

Collected Poems in English and French Company / Ill Seen Ill Said / Worstward Ho / Stirrings Still

Company / Ill Seen Ill Said / Worstward Ho / Stirrings Still Ends and Odds

Ends and Odds Endgame Act Without Words I

Endgame Act Without Words I Rockabye and Other Short Pieces

Rockabye and Other Short Pieces The Collected Shorter Plays

The Collected Shorter Plays The Complete Dramatic Works

The Complete Dramatic Works Three Novels: Malloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable

Three Novels: Malloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable The Unnamable

The Unnamable