More Pricks Than Kicks

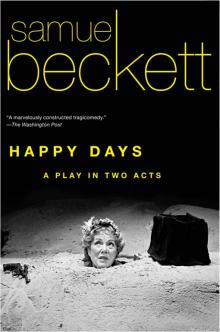

More Pricks Than Kicks Happy Days

Happy Days Breath, and Other Shorts

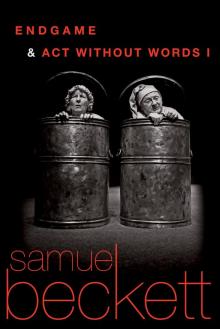

Breath, and Other Shorts Endgame & Act Without Words

Endgame & Act Without Words The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett

The Collected Shorter Plays of Samuel Beckett The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989

The Complete Short Prose, 1929-1989 Stories and Texts for Nothing

Stories and Texts for Nothing Waiting for Godot

Waiting for Godot Rockaby and Other Short Pieces

Rockaby and Other Short Pieces First Love and Other Shorts

First Love and Other Shorts How It Is

How It Is Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment

Disjecta: Miscellaneous Writings and a Dramatic Fragment Echo's Bones

Echo's Bones Texts for Nothing and Other Shorter Prose 1950-1976

Texts for Nothing and Other Shorter Prose 1950-1976 Three Novels

Three Novels Murphy

Murphy Mercier and Camier

Mercier and Camier Eleuthéria

Eleuthéria Selected Poems 1930-1988

Selected Poems 1930-1988 Dream of Fair to Middling Women

Dream of Fair to Middling Women Watt

Watt Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces

Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces The Complete Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett

The Complete Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Worstward Ho

Worstward Ho Collected Poems in English and French

Collected Poems in English and French Company / Ill Seen Ill Said / Worstward Ho / Stirrings Still

Company / Ill Seen Ill Said / Worstward Ho / Stirrings Still Ends and Odds

Ends and Odds Endgame Act Without Words I

Endgame Act Without Words I Rockabye and Other Short Pieces

Rockabye and Other Short Pieces The Collected Shorter Plays

The Collected Shorter Plays The Complete Dramatic Works

The Complete Dramatic Works Three Novels: Malloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable

Three Novels: Malloy, Malone Dies, The Unnamable The Unnamable

The Unnamable